Over the last twenty years, the proliferation of Internet access, coupled with the explosion of online social networks, has allowed people around the world to share their ideas and experiences with the click of a button. Beauty vloggers craft YouTube tutorials, gamers stream their performances live over Twitch, and journalists share and source news from across the world through Twitter. This web of content is always expanding—much of the information within it is true, however, plenty of it is not. How can we determine fact from fiction in this rapidly shifting information landscape? In response to these emerging concerns the Computing Community Consortium (CCC) organized the Detecting, Combating, and Identifying Dis and Mis-information scientific session at the 2020 American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Annual meeting this February.

Nadya Bliss

The AAAS session was organized and moderated by CCC Council Member Nadya Bliss (Global Security Initiative, Arizona State) and included:

- Emma Spiro (University of Washington), who examined the role of Misinformation in the Context of Emergencies and Disaster Events,

- Dan Gillmor (Arizona State University), who discussed Journalism and Misinformation,

- John Beieler (ODNI), who explained the Vulnerability of AI Systems,

- and CCC Council Member Juliana Freire (New York University) who served as the session discussant and tied together the impact of panelists’ topics.

Emma Spiro

Emma Spiro, an assistant professor at the University of Washington’s iSchool, began her presentation by highlighting the role of informal communication as one of the first channels available to spread hazard-related information. Rumors, defined by Spiro as a “story that is unverified at the time of communication,” are widely spread during crisis events as people seek out any knowledge that might help them. Rumoring can help to alleviate anxiety during information voids and acts as a form of collective sensemaking, but it can also lead to the spread of misinformation. Social media has transformed informal communication by expanding the pool of available information and increasing the speed at which information (and misinformation) can be spread.

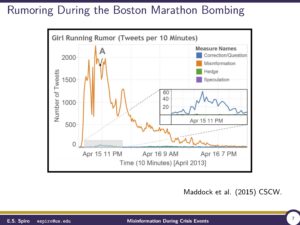

To highlight the rapid spread of misinformation, Spiro showed a graph (see below) that compared the amount of misinformation around one Boston Marathon rumor (read the full rumor on Snopes), in terms of tweets per ten minutes, to the amount of corrections or questions. There were far more tweets sharing misinformation related to this rumor—peaking at over 2000 tweets per ten minutes—than corrections/questions, which peaked at only around 60 per minute. In a crisis, misinformation can lead to serious harm, so it is critical we develop tools to detect and combat it. However, we are not only combatting the spread of information from folks who are well-meaning but misinformed, we also have to contend with malicious actors as the crisis information space is a prime target for disinformation and information operations.

Graph of Boston Marathon “Girl Running Rumor”

Spiro explained the distinction between misinformation and disinformation: misinformation refers to any false or inaccurate information while disinformation is a sub-category of misinformation created and spread specifically to deceive. Effective disinformation then becomes general misinformation and continues to be spread by unwitting consumers. Additionally, propaganda refers to the use of selective information, which may be true or untrue, to sway an audience towards or against a certain agenda, while information operations, “originally a military term that referred to the strategic use of technological, operational, and psychological resources to disrupt the enemy’s informational capacities and protect friendly forces,” has been used by social networking services to “refer to unidentified actors’ deliberate and systematic attempts to steer public opinion using inauthentic accounts and inaccurate information.”[1] In order to combat disinformation and identify information operations, researchers must consider the larger information ecosystem, not merely a single piece of content. Emma Spiro is a principle investigator for the University of Washington’s Center for an Informed Public, an interdisciplinary effort to turn research of misinformation and disinformation into policy, technology design, curriculum development, and public engagement. Learn more about their work on their website.

Dan Gillmor

Next Dan Gillmor, a long-time journalist and technology writer, addressed the role that journalists and the media play in propagating misinformation. While journalists often correct misinformation, Gillmor said that journalism is a frequently used attack surface for sharing disinformation and can become an amplifier for deceit. However, journalists are often unaware of being used due to inadequate detection and response. Deceitful people hack journalistic norms (e.g. false balance), trick news organizations into covering false information (e.g. through scientific “studies” paid for by vested interests), and leverage technology to promote false memes. Additionally, misinformation can provide ratings and act as click bait, increasing revenues but spreading untruths.

To combat this, journalists need to know how they are being used. FirstDraft, “a global non-profit that supports journalists, academics and technologists working to address challenges relating to trust and truth in the digital age,” has identified seven types of mis- and disinformation:

- Satire or Parody – No intention to cause harm but has potential to fool.

- Misleading Content – Misleading use of information to frame and issue or individual.

- Imposter Content – When genuine sources are impersonated.

- Fabricated Content – New content is 100% false, designed to deceive and do harm.

- False Connection – When headlines, visuals or captions don’t support the content.

- False Context – When genuine content is shared with false contextual information.

- Manipulated Content – When genuine information or imagery is manipulated to deceive.[2]

Gillmor said journalists should also rethink traditional norms (see this Gillmor written Medium post for one such example) and develop a better understanding of math and statistics to be able to put risk into context. Gillmor hypothesized that people get more misinformation from traditional media than from social media; however, this area needs more research, which will require the assistance of computer scientists.

Gillmor also called for an increase in media literacy, which is “the ability to access, analyze, evaluate, create and act on media messages in all forms,” and news literacy, “applying these critical thinking skills in the context of news information.” He argued that educators at all levels must be aware of and teach those forms of literacy to their students. Dan Gillmor is a co-founder of Arizona State University’s News Co/Lab, which “advances digital media literacy through journalism, education and technology.” Learn more about the work of the News Co/Lab on their website.

John Beieler

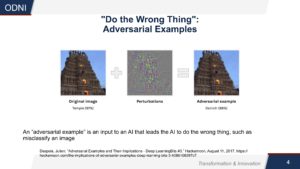

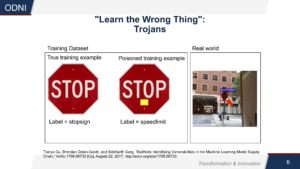

John Beieler, the Director of Science and Technology in the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI), discussed AI assurance and security. He also touched upon the role AI might play in combatting or facilitating the spread of misinformation in the future. AI assurance (a topic on which the CCC has held two recent workshops) includes topics such as validation, generalizability, and model drift, while AI security is concerned with issues like adversarial examples, model inversion, and data poisoning. An adversarial example “is an input to an AI that leads the AI to do the wrong thing, such as misclassify an image.” Trojans can poison a training data set, for example, teaching a self-driving system that a stop sign is a speed limit sign by adding a piece of tape to real-world stop signs. Detection and correction of these types of attacks, which cause an AI to learn, do, or reveal the wrong thing is a safety concern, As AI systems are more frequently enlisted to regulate social networks and source information, the validity of their operation and outputs becomes more critical to combating the spread of misinformation and we will need systems that are secure and assured.

Example of an “Adversarial Example”

Example of a “Trojan” Attack on AI

Juliana Freire

Following the three speakers’ presentations, discussant Juliana Freire, a faculty member of the NYU Center of Data Science, drew together the key insights from each presentation. We (including the media) are all vulnerable to misinformation and limiting its spread will require interdisciplinary efforts from fields like sociology, psychology, journalism, and computer science. Freire said that a major barrier to progress here is the lack of data—we need data to trace where misinformation comes from and to understand how it travels. While there have been some studies, they are often very limited and cover only how a specific ‘story’ was propagated using a small sample of posts on a specific social media platform. To really understand these phenomena we need more sensors that give a broader view of the problem, including news published online and information from multiple social media platforms. The former is readily available—computer scientists have developed techniques to crawl the web and discover information—but continuously crawling web pages is costly, and it is also difficult to discover the new websites that are dynamically created during misinformation campaigns. Therefore we need investment in data collection and data accessibility for researchers, as well as research to design methods to discover sources of misinformation in real time.

Obtaining social media data is more difficult, since typically large corporations own the data and they lack incentives to share it. One recent positive development was Facebook’s release of data “relating to civic discourse that were shared publicly on Facebook between January 2017 and July 2019” to vetted social scientists.[3] Yet more needs to be done to ensure that scientists can access these data, which will not only aid in understanding misinformation but also be used to create tools that guide journalists and news consumers.

During the Q&A portion of the session an attendee asked how to educate people who might be spreading misinformation. Emma Spiro discussed the work of the Center for an Informed Public (CIP) and their plan to hold town hall events across Washington state in order to get a broad understanding of how the state thinks about these issues. CIP is also developing a set of community labs and libraries across the state of Washington. Dan Gillmor said the New Co/Lab is working on a project with the Arizona PBS station that will educate viewers about media literacy. The Co/Lab is also working on a game targeted at helping senior citizens identify health-related misinformation.

Another attendee asked how we will be able to handle misinformation as technology becomes more complex and things like deep-fakes are shared more frequently. John Beieler replied that DARPA had a program on Media Forensics (MediFor) that focused on developing forensics tools to identify manipulated images. Beieler said that in terms of deep fakes there are some initial results that show they are not truly random and are therefore detectable with certain tools. The new DARPA SemaFor project addresses a similar topic and seeks “to develop innovative semantic technologies for analyzing media.” Detecting and combating mis- and disinformation is poised to be a hot topic for computing research going forward.

View all the slides from the Detecting, Combating, and Identifying Dis and Mis-information session on the CCC @ AAAS webpage. Nadya Bliss and Dan Gillmor participated in a debrief on the AAAS Expo Stage to further discuss the topic of misinformation—you can watch the full video of that debrief on YouTube here. John Beieler participated in live recording of the CCC’s Catalyzing Computing podcast at the AAAS Sci-Mic Stage that will be released soon. Listen to previous episodes of Catalyzing Computing here and subscribe through your preferred provider to stay updated when episodes are released.

Related Links:

- Americans’ Views of Misinformation in the News and How to Counteract It, Gallup/Knight Foundation (2018): https://kf-site-production.s3.amazonaws.com/publications/pdfs/000/000/254/original/KnightFoundation_Misinformation_Report_FINAL_3_.PDF

- “Disinformation as Collaborative Work: Surfacing the Participatory Nature of Strategic Information Operation,” Kate Starbird, Ahmer Arif, Tom Wilson via Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction (2019):http://faculty.washington.edu/kstarbi/Disinformation-as-Collaborative-Work-Authors-Version.pdf

- Information Disorder: an Interdisciplinary Framework, Claire Wardle and Hossein Derakhshan via First Draft: https://firstdraftnews.org/latest/coe-report/

- “Introducing the Transparency Project,” Nancy Shute, Science News: https://www.sciencenews.org/blog/transparency-project/introducing-transparency-project

- “Less than you think: Prevalence and predictors of fake news dissemination on Facebook,” by Andrew Guess, Jonathan Nagler, and Joshua Tucker via Science https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/5/1/eaau4586

- Lexicon of Lies: Terms for Problematic Information, Caroline Jack, Data & Society https://datasociety.net/pubs/oh/DataAndSociety_LexiconofLies.pdf

- Network Propaganda: Manipulation, Disinformation, and Radicalizationin American Politics, by Yochai Benkler, Robert Faris, and Hal Roberts https://www.oxfordscholarship.com/view/10.1093/oso/9780190923624.001.0001/oso-9780190923624

- The Oxygen of Amplification: Better Practices for Reporting on Extremists, Antagonists, and Manipulators Online, Whitney Phillips, Data and Society: https://datasociety.net/output/oxygen-of-amplification/

- “The science of fake news,” David M. J. Lazer, Matthew A. Baum, et al. via Science https://science.sciencemag.org/content/359/6380/1094

[1] Caroline Jack, Lexicon of Lies: Terms for Problematic Information, Data & Society Research Institute, 2017, p 6. https://datasociety.net/pubs/oh/DataAndSociety_LexiconofLies.pdf

[2] https://firstdraftnews.org/latest/fake-news-complicated/

[3] Jeffrey Mervis, “Researchers finally get access to data on Facebook’s role in political discourse,” Science Magazine, 2020. https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/02/researchers-finally-get-access-data-facebook-s-role-political-discourse